Here was Denard Robinson, a freshman at football-delirious Michigan, with his free-flowing dreadlocks popping out from the back of his helmet and his shoelaces untied.

And here was a problem.

Not a problem with a position change or a coaching change. That would come later. Not a problem with an injury -- like the one this season that was kept secret for months and landed him in the hospital.

No, this problem was quite simple compared to all that:

No one could understand a word the guy was saying.

Robinson was young, unsure of himself, and, according to center David Molk, "a scared little kid who didn't know what to do."

And this kid wanted to play quarterback? At Michigan? A school known for producing guys that win Super Bowls?

Sure he had the guts. He grew up in a tough section of the Fort Lauderdale suburb of Deerfield Beach, where the realties of life require faith and tenacity. It's not too far from Riviera Beach, where quiet-but-beloved receiver Anthony Carter was raised.

But Anthony Carter could go an entire collegiate career without speaking. Not Robinson. Not if we wanted to win the starter's job.

Yet Robinson, shy by nature and careful with every word spoke nearly as quickly as he ran. His southern drawl -- described by teammates as "Talking Florida" was barely discernable to Molk, who struggled to understand snap counts or checks Robinson made at the line of scrimmage.

Molk knew if this quarterback-center relationship was ever to work -- if Robinson was ever to work -- someone was going to have to slow down.

"I told him to take out his mouthpiece when he talked," Molk says now, three years later, in a hotel ballroom in New Orleans, where Michigan will play in its first BCS bowl game in five years in Tuesday night’s Sugar Bowl against Virginia Tech.

"I couldn’t understand anything."

Three years later, after many tough losses, coaching dramas and injury scares, the tentative kid from Deerfield Beach has become the face of Michigan football. And if he stays healthy, Denard Robinson has a chance to leave campus next year as one of the best ever to wear the winged helmet.

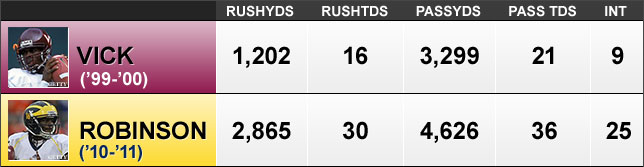

It's somewhat appropriate that Michigan is playing Virginia Tech Tuesday, as Robinson's childhood hero was Blacksburg hero Michael Vick. Robinson patterned his game after Vick but realized he wasn't as big and didn't have the arm. College offers -- especially to play quarterback -- were almost non-existent. Recruiters considered Robinson more of an athlete, a gifted runner with a knack for making enough people miss to get him into the open. But how many of those come out of Florida every year? Plenty.

"When I got to high school, I was like, 'Hopefully, I can get to a Division II school,'" Robinson says. "I was undersized and I didn't know anyone would look at me. I was like, 'Hopefully, I can just get out of the city of Deerfield.'"

Rich Rodriguez, the mastermind behind the spread offense, saw Robinson as a perfect fit for the new, free-wheeling system he was installing at Michigan. Robinson had run more of a pro-style set at Deerfield Beach High School, but he figured if Rodriguez wanted to bring him to Michigan, he wasn't going to argue.

The coach was sold, but Molk, who would go on to be named the nation's top collegiate center in his final year at Michigan, had his doubts.

"He'd sit back there as the quarterback and he'd be so scared, he wouldn't catch the snap half the time," Molk says.

If nothing else, Robinson had his legs to bail him out. He was far from polished and struggled with throwing the football, but he could run. His feet, unlaced cleats and all, could take Robinson places. Even if his hands and throwing weren’t sure, "Shoelace" (as one of his football coaches back in Florida crowned him) had a second line of defense.

"He'd just go -- that's what he does," Molk says. "He can make a play out of nothing."

His first play in a game as a freshman in 2009 against Western Michigan was a perfect example.

As had become routine in practice, Molk's snap hit Robinson in the hands and then fell to the ground. But it bounced back up and Robinson grabbed the ball and ran. He started right, escaped the grasp of a defender who tried to make an ankle-tackle. He cut back, weaving through Western Michigan players before finding an open lane and running to the end zone 43 yards later. It was a 'Wow' moment for all Michigan fans. This was not a place used to seeing that kind of speed from a guy under center.

Robinson may have been exciting, but he was also one-dimensional. He split time at quarterback with fellow freshman Tate Forcier, who was seen as more durable and more reliable in getting the ball downfield. So on the occasions when Robinson entered the game, it was to run. If Forcier was forced out of a game temporarily, he often returned to raucous cheers, quickly becoming the preferred choice between the two first-year quarterbacks. In the all-important Ohio State game, Robinson lined up at wideout.

While Forcier appeared unflappable, Robinson remained reserved and at times uncertain. He preferred to remain in the shadows if possible, figuring if something had to be said, someone would say it.

It just wouldn't be him.

"I remember just talking to him and he was shy," wide receiver Roy Roundtree says. "He really didn't talk."

That would have to change.

Most Michigan fans were surprised when Robinson won the starter's job as a sophomore. But the bigger surprise came when Robinson showed a new passer's touch.

Against Notre Dame in his second start, Robinson accounted for 502 of Michigan's 532 offensive yards, making him the talk of the nation and the front-runner for the Heisman Trophy. Within two days of the win in South Bend, the Michigan sports information office had received 100 interview requests. On average, another 25 rolled in every week for the 11 weeks that followed.

Robinson was among the most electrifying playmakers Frank Beckmann had ever seen. Beckmann, a veteran radio play-by-play man who has called Michigan football games since 1981, had seen all the greats from Charles Woodson to Desmond Howard to Anthony Carter roll through Ann Arbor. Never in his career had he seen anything like Denard Robinson.

"You never know what to expect," Beckmann says. "You can't just assume a play is over at any time."

Early in Robinson's career, Beckmann used a high-pitched, 'Whoop' to describe every time the elusive quarterback made someone miss. But soon, it became too much to keep up with.

"After a while, I said, 'Let's just call it and let him run,'" Beckmann says.

Robinson was a celebrity around Ann Arbor, where his fellow Michigan students embraced him on a daily basis. Between his hair, his popular No. 16 jersey and his untied laces, T-shirt companies produced apparel with his uniform number and his shoes, pitching them out of the back of trucks and in privately owned storefronts.

Perhaps for the first time, he knew he had arrived.

"That was a different feeling," Robinson says. "It gives you the feeling you're accomplishing something you always dreamed of. I always dreamed about fans screaming my name. I didn't know if it would come true and now, it's coming true."

By the end of the year, Robinson had amassed an NCAA-record 1,702 rushing yards for a quarterback and threw for another 2,570, despite missing time with injuries in 10 of the 13 games he appeared in.

But just like defenses were unprepared for Robinson, it seemed everybody, including Robinson, was unprepared for the Denard craze. He seemed fragile -- unable to withstand the brutal Big Ten schedule without injury. Michigan fans weren't sold on Rodriguez, and saw No. 16 as a cure-all when he scored but a symptom when he couldn't lead a comeback like the daredevil Forcier.

Robinson often appeared uncomfortable. He was still shy. He avoided media attention as much as possible. For each of the 14 touchdowns he scored as a sophomore, he ended each run by kneeling in the kneeling in the back of the end zone.

"Everybody is praising me at that time -- I want to give (God) the praise because He is the one who put me in the position to do what I do."

But a breakout year wasn't enough. The worst three-year stretch in Michigan football history cost Rodriguez his job, culminating in an embarrassing 52-14 Gator Bowl loss to Mississippi State a year ago. Robinson knew a new coach would likely bring a new system, and he wondered how he would fit in.

Robinson talked to his parents. He spoke with friends and other family members. But his circle also included Rodriguez, who knew how much Robinson loved Michigan.

Rodriguez was clear in his message.

"Coach Rod told me if I'm going to stay here, give in, buy in 100 percent -- just don't go halfway. Go all in," Robinson recalls.

After briefly considering leaving, Robinson met with his teammates, who by now had become a second family.

"He was kind of pissed," nose tackle Mike Martin says of the meeting. "He was like, 'I can't believe any of you guys would think I would leave. You guys are my brothers, my teammates. I'm not going to leave you.'"

It was a risk. Brady Hoke came to Michigan from San Diego State, bringing offensive coordinator Al Borges and his pro-style offense with him. There would be adjustments to be made. Notre Dame came to Ann Arbor in September and at first, Robinson looked robotic -- thinking for the split-second it used to take him to get moving.

"I told him from Day 1 he wasn't going to rush for 1,700 yards because we had to keep him in one piece if it killed us," Borges says. "That would be easy for a kid to say, 'Hey, what the heck.' Not him."

As accepting as Robinson appeared on the outside, he was forced to answer questions about his role. Reporters asked if he felt limited or if he felt he could be effective in a system in which his rushing attempts per game would sometimes be cut in half.

His teammates had worries as well.

"That's what he's good at -- he can run," Molk says. "Obviously, it was kind of concerning of what we were going to do to get yards out of his offense."

Robinson struggled with his footwork, forcing himself to slow down and not use his legs as much as he had under Rodriguez. At times, he threw without having his feet firmly planted. On other occasions, he made bad decisions, throwing a career-high 14 interceptions while he struggled to fully understand the new offense.

Part of growing as a quarterback also meant growing as a leader. He had to be more assertive in the huddle. He had to accept the fact that even though Michigan's roster was peppered with more experienced veterans -- especially on the defensive side of he ball -- he was Michigan's identity.

And as much as Borges tried to limit the hits his quarterback took, Robinson still dealt with injuries -- first with his elbow, then with his hand and most severely, a staph infection in his throwing arm.

The staph infection wasn't revealed until after the regular season when Hoke quickly told reporters exactly what Robinson had endured for three weeks.

"There was some concern," Hoke says.

Robinson spent a night in the hospital with the injury, which he kept a secret even from his teammates. Nobody in the program revealed how the infection occurred, but it may have been started with a scrape on a patch of field turf. As painful as the infection was, Robinson never made issue of it, and even refused to tell close friends when asked about it. There was also an abdominal injury that went under the media radar.

"There was a lot going on, but we had to fight through it," Robinson says. "We just had to keep fighting."

His teammates followed their leader, producing Michigan's first 10-win season since 2007. Although Robinson is slow to take credit for the turnaround, his play -- and his demeanor around his teammates -- became increasingly evident.

"He's the leader of our team and when he's in the huddle, he's demanding," Roundtree says. "He's someone I look up to even though he's younger than me."

Robinson led Michigan to a 10-2 regular-season finish, capped by the Wolverines' first win over rival Ohio State since 2003. Despite running for 600 fewer yards than he did last season, when he finished sixth in the Heisman balloting, Robinson's maturation yielded big results. Robinson flourished throwing the ball in Michigan's final three games, when he was a combined 31-for-45 passing for 439 yards and only two interceptions.

Two years after drawing groans every time he threw the ball, Robinson was a true threat with his arm.

Robinson filed paperwork with the NFL Draft Advisory Board in December, but asked in the days leading up to the Sugar Bowl whether he intended to return to Michigan, Robinson flashed his trademark smile.

"Oh yeah," he says. "I expect to be back."

If Robinson repeats his 2011 stats as a senior, he would finish his Michigan career ranked second all-time in rushing yards behind Mike Hart. His would rank second in rushing touchdowns behind Anthony Thomas. He would rank third in passing yards behind Chad Henne and John Navarre. He would rank fourth in passing touchdowns behind Henne, Navarre and Elvis Grbac. And he would become Michigan's all-time leader in all-purpose yards with more than 12,000. Not bad at a school that produced Jim Harbaugh, Brian Griese, Todd Collins and Tom Brady.

But few are ready to put Robinson in that group. And the Deerfield Beach product knows it.

"I can't control what other people think," Robinson says. "I'm just doing whatever I have to do to show people I am a quarterback."

One person who doesn't need convincing? Virginia Tech coach Frank Beamer, who called not recruiting Robinson a mistake. Beamer, who coached Robinson’s childhood idol, Vick, during his collegiate career, now holds Robinson in the same category as his former star.

"He's certainly the same type of athlete," Beamer says. "But I'll tell you one thing -- that ole boy can do it. He can flat out do it."

And for being a kid Molk remembers as "fresh off the boat from Florida" who struggled to be understood, the growth spurt has been nothing short of amazing. But the most amazing chapter might be starting right now. Robinson's next two games will be in NFL stadiums -- Tuesday in the Superdome and then in the fall against Alabama at Cowboys Stadium.

"That's what I'm trying to work for -- that's why I'm trying to be a better quarterback and passer," Robinson says. "Hopefully, I can have the blessing of playing quarterback in the NFL some day, just like Michael Vick."

Tuesday night, in the building where Vick had his most memorable college moment in the BCS title game against Florida State, Robinson will have a chance to create similar memories. And if he's anything like his idol was that night, he can spend the entire off-season letting everyone else do the talking.

-- Jeff Arnold can be reached at jeffarnold24@gmail.com or follow him on Twitter @jeff_arnold24.