An old grainy YouTube video is the only visual evidence we have.

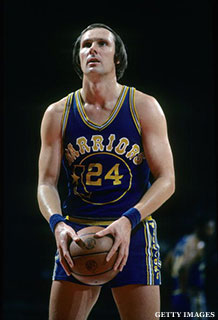

George Johnson, a slender 6-11 center, steps to the free throw line. He dribbles the ball three times, takes a breath, and in a simple, fluid motion, flings the ball underhand toward the hoop. The ball swishes so gently it's like the net's apologizing for being there.

"It was after practice one day and a teammate and I were messing around," Johnson recalls. "Rick [Barry] watched me shoot a few underhand and said to me, 'George, if you're interested in learning, I'll teach you.'"

Attempting his free throws overhand, Johnson shot 53 percent his first two years in the NBA, hovered around 65 percent the next two, and then allowed Rick Barry to teach him his patented underhand floater during the 1976-77 season.

After only a "month or two" of working with Barry after practice, Johnson started shooting free throws underhand in games, and by the end of the season, was making 80 percent of his attempts.

"I remember that first night clearly," Johnson says. "Instead of putting the ball over my head, I spread my feet shoulder length apart, I remembered everything Rick told me: Cock the wrists, take the ball, line up the seams, and aim just above the rim. So I did that, and it wasn't a swish, but I made it. The confidence grew from there."

If you don't remember Johnson's game, he was an athletic, defensive-minded big man known for his shot-blocking ability, leading the NBA three times in 1978, 1981 and 1982. He set screens, grabbed rebounds, threw outlet passes, and rarely, if ever, had a play called for him.

Johnson was, for all intents and purposes, the DeAndre Jordan of his generation. An alley-oop catching, rim protecting 7-footer of awe-inspiring athleticism.

Minus the occasional jump hook, the George Johnsons and DeAndre Jordans of the NBA score their points in two ways: Dunks and free throws.

DeAndre Jordan shot 374 free throws last season. He missed 214.

"It took George Johnson one season to go from a poor free throw shooter, to an 80 percent free throw shooter," Barry says. "It took me working with him roughly one full season. There is a better way to do it. It comes down to a pride issue."

That point was perhaps best articulated by Shaquille O'Neal, another brutal foul shooter, who once said, "I will shoot 30 percent before I shoot underhand, I promise you that."

It's a mentality that Barry cannot grasp.

"You're doing a disservice to yourself, a disservice to your team, if you aren't making these shots," he says. "I can't understand how anyone can live with themselves if they can't shoot 80 percent from the free throw line."

I wonder how many times, during the course of NBA history, a team executuve did this math:

If Player X makes 75 percent of his free throws instead of 55 percent, our team would win X additional games per year.

For whatever reason, basketball's hierarchy doesn't seem to care much about free throws, even though it's the only part of the game where the variables are the exact same, every single time.

If they cared, really cared, they'd try anything possible, right? They'd do some research, take a "maybe On-Base Percentage is a more relevant statistic than Batting Average" approach to what seems a very fixable problem.

Fifteen feet. One ball. No wind. Inflatable clapping sticks in the background half the time. Cool. Let's do this.

But over the last 35 years, not one NBA team has ever reached out to Rick Barry. The sixth best free throw shooter of all-time who also shot the ball in a completely different fashion than everyone else.

And while Barry's not exactly known for his modesty, it's hard to argue with his results.

"If you look at my statistics, and analyze them, my last six years, when I made a change in my technique, refined it, I shot over 92 percent," Barry says. "My last two seasons I think I only missed 19 free throws in both seasons.

This is true. Barry went 303 for 322 those two seasons with Houston.

"I shot 94.7 percent and 93.5 percent, and I was only shooting about two free throws a game," he says. "Had I had that technique earlier in my career when I was shooting 10-12 free throws a game, I think the numbers over the course of my career would've been staggering."

Which brings us to DeAndre Jordan and the numerous other professional basketball players who have shown zero improvement shooting free throws overhand (or overhead, if you prefer) throughout their careers.

What basketball people don't realize is that there's a reason big men like DeAndre, Andre Drummond, Andrew Bogut, Dwight Howard, and the NBA's long list of atrocious free throw shooters spend thousands of hours practicing free throws, waiting for their inner Mark Price to emerge, but never see results.

The problem isn't mental, it's physical, and as long as these players continue shooting overhand, they will never, no matter how many hours they spend in the gym, improve.

Dr. Larry Silverberg has studied many important things. He's published papers on, "Transpermanent magnetic actuation for spacecraft pointing, shape control, and deployment," "Autonomous coordination of aircraft formations using direct and nearest-neighbor approaches", and "Cellular growth algorithms for shape design of truss structures," to name a few.

But Silverberg, a mechanical and aerospace engineering professor at North Carolina State, has also spent an exorbitant amount of time studying how basketballs go through hoops.

His basketball-related publications include "Optimal targets for the bank shot in men's basketball," "Numerical analysis of the basketball shot," and in 2008, he published, "Optimal release conditions for the free throw in men's basketball" in the Journal of Sports Science.

"In an overhead shot, the motion of the body starts with the legs, torso, arms, hands, in a complex sequence of motions," Silverberg says. "The beauty of the underhand shot, although you're releasing it farther from the basket in a sense, because you're releasing it lower, is that you have one smooth motion."

"One motion is much easier than four that have to be sequenced. So when you perfect it, you'll end up with a release speed that has lower statistical variation than the overhead."

OK, time for a little science. Don't worry, it'll be quick.

Silverberg says that what Barry and others have observed is that they can make quick progress in building "kinesthetic" memory with the underhand shot. In free throws, the most important variable is the release speed of the ball, which is a "kinematic" variable (the other variables -- height of release, release angle -- are geometric).

Release speed requires kinesthetic memory and needs to be consistent for shots to fall, which is why the underhand shot makes so much sense. The motion can be learned and cemented in a players' kinesthetic memory in weeks, whereas an overhand shot for a 7-footer is an incredibly complex motion that most athletes, due to their lack of coordination and poor fundamentals, will never be able to execute consistently.

It's important to note that the guys who struggle with free throws aren't trained shooters. Dirk, Durant, and Aldridge are big guys that make their money shooting the ball, but why does a defensive-minded big man need to shoot the ball overhand?

Andre Drummond doesn't need to hit 20-footers. He needs to grab rebounds, block shots, make layups, and when the other team wraps him up and makes him go to the line, he needs to put points on the board.

Detroit was a below-average team last year, but Drummond and Josh Smith combined to make only 297 of their 629 foul shots (47 percent). If they shoot 70 percent, that's an extra 143 points. How many additional wins do those 143 points net the Pistons? How many skin cells does Mo Cheeks save from not fiercely rubbing his temples every time Smith lofts two shots off the back of the rim?

What if Drummond had started shooting underhand at 16? Where would he be percentage-wise now?

The most important takeaway is this: If DeAndre or Drummond started practicing the underhand stroke today, there's a strong likelihood that they'd improve their free throw percentage by 20 percent to 40 percent by playoff time -- it doesn't take years, it takes months.

"If someone were interested, I would certainly be happy to teach them what I know, but Rick was really good at it," says Johnson, who consistently shot free throws with percentages in the 70s after adopting the underhand method. "It took me a minute to get my head around it and it apply [the technique], but once I did, it became easier and easier to shoot, and I used to look forward to getting fouled so I could go to the line, instead of the reverse."

There's only one guy that can teach the underhand free throw (two, if you include Johnson), and Rick Barry's not wildly popular in NBA circles.

"I ran into Shaq's shooting coach outside the Staples Center one time," Barry says. "He said, ‘So we tried the underhand free throw and it didn't work.' I remember looking at him thinking, 'What do you mean you tried the underhand free throw? Who's gonna teach him my technique? You?'"

But one thing Rick Barry can do better than 99.9 percent of human beings on the planet is shoot a basketball, and it's shocking, considering his unique method and statistics, that nobody has thought to hire him to work with the Andrew Boguts of the world.

The main reason for reluctance, of course, is that in a game of panache, the underhand free throw is probably the least "sexy" thing you can do on a basketball court.

Even Johnson admitted, "I don't think big strong guys like Andre [Drummond] would want to put the ball between their legs and aim it as the basket."

But I refuse to believe that if Doc Rivers went up to DeAndre Jordan tomorrow at practice and said, "Look, DeAndre, we got this old cranky guy coming in that's going to teach you how to shoot free throws underhand. Kevin Garnett is going to talk a lot of s***. A lot. Other guys will too. But we're confident we can get you above 60 percent by March, maybe higher, and have you shooting above 70 percent the rest of your career, maybe as high as 80 percent. We have a chance to win an NBA championship, and I want you on the court during crunch time, not on the bench because you're unwatchable from the foul line. It's only going to take an extra hour or two every day after practice. Now let's get out of here. Blake and Chris are waiting for us at Tender Greens."

What would DeAndre Jordan say to that?

"I felt empowered by [the underhand free throw]," says Johnson, who shot a career-best 81.5 percent from the line in his second-to-last season in the NBA. "It made me stand out."

And DeAndre Jordan likes to stand out. He wants the same endorsement deals as Blake Griffin, wants the attention, and most importantly, wants to win.

Because if DeAndre Jordan starts swishing free throws underhand, the next wave of big men coming up through the AAU circuit will do the same.

And if he makes 75 percent of his free throws, the Clippers chances at a championship go up by X percent.

How many chances does a player have to revolutionize his sport?

What if DeAndre Jordan put his feet shoulder length apart, lined up the seams, and in one motion, made the underhand free throw "cool"?

-- Follow Tim Livingston on Twitter @timlikessports or email him timlivingston0sports@yahoo.com.