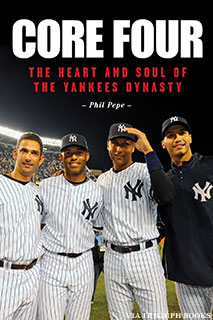

The New York Yankees were in free fall, having failed to win a World Series in 17 years and had not played in one in 14 years -- the Bronx Bombers' longest drought since before the days of Babe Ruth. Then along came four young players whose powerful impact returned the franchise to its former glory. They were a diverse group from different parts of the globe: Mariano Rivera, a right-handed pitcher from Panama, who was destined to become the all-time record holder in saves and baseball’s greatest closer; Derek Jeter, a shortstop raised in Kalamazoo, Michigan, who would become the first Yankee to accumulate 3,000 hits; Jorge Posada, an infielder-turned-catcher from Puerto Rico, who would hit more home runs than any Yankees catcher except the legendary Hall of Famer Yogi Berra; and Andy Pettitte, a left-handed pitcher born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, who would win more postseason games than any player in baseball history. This excerpt of Core Four by Phil Pepe reveals how the Yankees signed Rivera and might have lost him before he appeared in a major league game.

Major league baseball scouts were not exactly beating a path to Panama in 1990, not like they were to San Pedro Macoris, the Dominican Republic; Santurce, Puerto Rico; or Caracas, Venezuela. In 1990, you journeyed to Panama to discover future stars of World Cup soccer or for the shrimp and sardines, not for baseball players.

On February 17, 1990, when the Yankees signed an undrafted, free agent amateur named Mariano Rivera from the tiny fishing village of Puerto Caimito, Panama, a transaction deemed so inconsequential it never so much as made the agate of the New York newspapers. Only 24 Panamanians had ever appeared in a major league game, most of them up for little more than the proverbial cup of Jaramillo Especial.

On the list of big leaguers from Panama were former Yankees Hector Lopez and Roberto Kelly; catcher Manny Sanguillen, a mainstay for the Pittsburgh Pirates that won six National League East titles and two World Series in the 1970s; Rennie Stennett, who tied a major league record on September 16, 1975, when he banged out seven hits for the Pirates in a game against the Chicago Cubs; and one Hall of Famer, Rod Carew, whose Panamanian mother gave birth to him on a racially segregated train in the town of Gatun in the Panama Canal Zone. When Carew was 14, his family migrated to the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, where he attended George Washington High School, which also produced Manny Ramirez and Dr. Henry Kissinger.

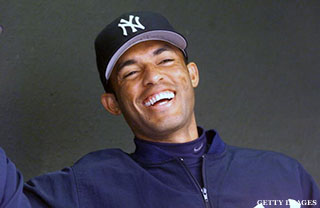

Mariano Rivera was born on November 29, 1969, four months after Apollo 11 landed on the moon, 44 days after the New York Mets won their first World Series in a resounding upset of the heavily favored Baltimore Orioles, and eight days after the birth of Ken Griffey Jr., half a world away. As a child, young Mariano whiled away the idle hours playing baseball, but not with any thought of making it a career. Soccer was his game. Baseball was fun, a diversion played with baseballs handmade of fish netting and electrical tape, bats constructed from tree branches, and gloves formed out of milk cartons. When he was 12, Mariano's father bought him his first real glove. His formative years were good times, so good Mariano didn't realize he was poor.

"I didn't have much," he once said. "I didn't have anything. But what we had, I was happy. My childhood was wonderful."

Finished with Pedro Pablo Sanchez High School at 16, Mariano did what most Panamanian boys his age did: he went to work. Six days a week he toiled on a commercial fishing boat captained by his father. On the seventh day he played sports.

"On the boat, I liked looking at all the different fish," he said. "But my father's life was not for me. There's no future in fishing."

Perhaps he could escape as a professional soccer player. Baseball was not an option, but he continued to play for fun with Panama Oeste, a local amateur team.

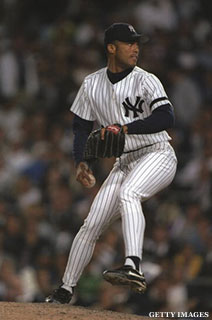

If it was fate that brought a man named Herb Raybourn, director of Latin American operations for the New York Yankees, to Puerto Caimito, where he first saw Rivera, a 155-pound shortstop -- "He had a good arm and good hands, but I didn't think he could be a major league shortstop so I passed on him." -- it was good fortune that sent Raybourn back to Puerto Caimito to check out reports about a promising pitching prospect named Mariano Rivera. Raybourn was confused. The Mariano Rivera he knew in Puerto Caimito was a shortstop, and no prospect. Nonetheless, Raybourn returned to the tiny fishing village and arranged a workout for the young shortstop-turned-pitcher.

What Raybourn saw hardly blew the scout away, a pitcher topping out at 84 miles per hour, not the stuff of legend or future stardom. But Raybourn saw something special in the skinny right-hander: a joy for the game and a strong desire to excel. He also saw rare athleticism and an easy, fluid pitching motion that caused the baseball to jump out of his hand and enable him to get excellent movement on his pitches.

Raybourn reported his findings to the Yankees, who authorized him to offer the young pitcher a signing bonus of $3,000, tantamount to a king's ransom to a child of Puerto Caimito, Panama. Rivera eagerly accepted the offer, hoping this was his chance to avoid the life of a fisherman. It also was the only offer he received.

"I was there the year before and I passed on him," said Raybourn. "I went back a year later and we got him. Why didn't any of the other scouts sign him before I got back to Panama?"

Why, indeed!

Somewhat frightened and extremely naive -- he had never been out of Panama, had never been on an airplane, and he spoke no English -- Mariano, considered nothing more than a fringe prospect, flew to Tampa to join the Yankees affiliate in the Gulf Coast Rookie League, the lowest rung on the team's minor league ladder.

Rivera's Tampa Yankees teammates were future major leaguers Russ Springer, Ricky Ledee, Shane Spencer, and the Yankees' first-round draft pick that year, Carl Everett. Rivera's manager was 29-year-old Glenn Sherlock of Nahant, Massachusetts, a catcher who had been the 21st-round selection of the Houston Astros in the 1983 amateur draft and who had spent seven minor league seasons in the Astros' and Yankees' farm systems without ever reaching the major leagues.

Sherlock, now the bullpen coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks, remembers the young Rivera as "very quiet -- he didn't speak a lot of English -- a very nice kid that went about his business in a professional manner.

"Obviously we didn't know at that time that he was going to be maybe the greatest relief pitcher of all time. I don't know if anybody is that smart. What we did see was that he had a very good work ethic and he did a lot of the little things like the bunt defenses and the pitchers fielding practice. He put a lot of effort into it. He was an extremely good athlete.

"Hoyt Wilhelm [the Hall of Famer, one of the great knuckleball pitchers of all time and a pioneer relief pitcher for 21 seasons in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s] was our pitching coach and he used to play a game with the pitchers so they could have some fun. He'd let them bat and shag and Mariano could really hit and he could really play the outfield. He was clearly one of the best athletes we had on the team."

As his first season was winding down, Rivera had pitched in 21 games and had the lowest earned run average in the league, but he was five innings short of qualifying for the league ERA title, for which the Yankees offered a wristwatch and a bonus of $500.

"We had a doubleheader on the last day of the season," Sherlock recalled. "We spoke to Mitch Lukevics [director of minor league operations for the Yankees] and talked about starting Mariano in one of the games. We got an okay and Mariano pitched a seven inning no-hitter, which was pretty amazing."

While he still was not considered a hot prospect, the no-hitter, a 5–1 record, an ERA of 0.17, 17 hits allowed, and 58 strikeouts in 52 innings, could not be overlooked. At least it caught their attention in the Bronx and Tampa (where the Yankees' player development staff is located) and it elevated, at least slightly, Rivera's status.

No longer merely a fringe prospect, Rivera was moved up to Class A Greensboro in the South Atlantic League the following season. At Greensboro, Rivera split his time almost equally between starting and relieving. Despite a record of 4–9, he continued to impress and progress with a 2.75 ERA, 123 strikeouts, and only 36 walks in 114 2/3 innings. It caught the attention of Yankees manager Buck Showalter, who deemed Rivera's strikeout-to-walk ratio "impressive in any league."

Showalter was not alone in his judgment. The Yankees brain trust concurred, bouncing Rivera up to Fort Lauderdale in the high A Florida State League in 1992. The Yankees decided he was now a full-fledged starter. By midseason, Rivera had made 10 starts, had a record of 5–3, a 2.28 ERA, 42 strikeouts, and an especially impressive five walks in 59 1/3 innings. Then he faced his first crisis.

Attempting one day to improve the movement on his slider by twisting his wrist, Mariano felt something snap. He had damaged the ulnar collateral ligament in his pitching elbow, requiring surgery and abruptly ending his season.

"People think he had Tommy John surgery, but he didn't," said Gene Michael, the Yankees' super-scout/adviser (as well as former player, manager, and general manager).

No less an authority than Dr. Frank Jobe, the legendary orthopedist who pioneered ligament replacement (or Tommy John) surgery, made the diagnosis and ruled out the procedure which would have sidelined Rivera for at least a year.

"The ligament was frayed and Dr. Jobe cleaned it up," said Michael.

As a result, Rivera's rehabilitation did not cause him to miss the 1993 season. However, the injury did present the Yankees with a dilemma. Rivera's rehab coincided with the MLB expansion draft required to fill the rosters of two new teams, the Colorado Rockies and Florida Marlins. While they still didn't consider him a top prospect -- "He had a straight fastball, no cutter, and no movement," remembered Gene Michael. "He was mediocre at best." -- the Yankees thought enough of Rivera to protect him on their 40-man roster. However, they failed to include him on their protected list for the expansion draft.

In hindsight, the Yankees' Mark Newman, who has been with the team since 1989 and is currently the senior vice president of baseball operations, remembered there were few back then who were on the Rivera bandwagon.

"When we signed Mariano in 1990," said Newman, "I don't remember anyone saying, ‘This guy is going to be a major leaguer.' He was a very good athlete and he could throw it over the plate, but nobody wrote out the Mariano development plan that said he would someday throw 98 miles per hour, have the finest control on the face of the planet, would learn a cutter, and, oh by the way, that's all he's going to throw."

Either the Rockies or the Marlins could have taken him, a thought that sends shivers up the spine of Yankees front-office personnel and fans. But to their everlasting regret, both the Rockies and Marlins passed on Rivera and he resumed his career with a step back to the Gulf Coast Yankees and Greensboro.

At Tampa and Greensboro, Rivera appeared in 12 games, all starts, winning just one game and losing one, but posting earned run averages of 2.25 and 2.06 and holding batters to a .208 average. His star was beginning to rise in the Yankees galaxy.

-- Excerpted by permission from Core Four by Phil Pepe. Copyright (c) 2013 by Phil Pepe. Published by Triumph Books. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase from the publisher, Amazon, Barnes & Noble and iTunes.