The SEC developed into the premier conference in college football for several reasons. One factor was that it was the first to stage a conference championship game. In How The SEC Became Goliath, veteran sportswriter Ray Glier examines the dynamics of why this game boosted the conference.

Roy Kramer did not sleep well the last week in November 1992. How could he? It was partly his bright idea to widen the moat in front of undefeated Alabama and make the Tide play one more conference game that season. In other years, the 11–0 Crimson Tide would be joyriding toward the Sugar Bowl to play Miami for the national title. But now the top was not down for Bama, the sun was not out, and there was no joyride. The Tide were preparing for another SEC game and muttering all the way that somebody was out to get them.

Kramer, the SEC commissioner, with the backing of the university presidents in the SEC, had concocted this thing called the SEC Championship Game. Who had ever heard of such a thing in Division I? It looked reckless to make the SEC regular-season champion play another game, and Gene Stallings, the Alabama coach, did not let Kramer forget about it that week.

"Gene said, ‘We're eleven and oh and we haven't won nothin'," Kramer said. "He was right. They had the best record in the conference, but they were not conference champions."

The day he found out the SEC was adding a twelfth game for the winners of the two divisions, plus going to an eight-game conference schedule, Stallings emerged from the meeting where those details were finalized and declared in a somber tone, "The SEC will never win another national championship."

Majors had said the same thing in 1989, but for other reasons. The SEC was starting to stamp out more and more NFL-caliber players, particularly on defense. Crowds were revved up; stadiums shook and threatened visiting teams. It was hard to win . . . anywhere.

And now the caretakers of the SEC had created an obstruction for its champion. Ohio State, Michigan, Notre Dame, Miami, Florida State, and Southern Cal, the other powerhouses, could relax after eleven games. Alabama, and the SEC teams that would follow it to the gallows of this thing called the SEC Championship Game, had to reboot and win again in a conference postseason game proposed by Stallings's own conference. It meant Alabama, just a week after playing the hysteria-filled Iron Bowl with Auburn, would have to play again on Legion Field against Steve Spurrier and Florida.

In the same meeting from which Stallings emerged with much anguish, Spurrier looked across the table at Kramer and wondered if Kramer was violating some sort of NCAA law. "Is that legal," the Ball Coach asked of the proposed championship game. When the other conferences found out about the SEC's plan for a title game, they discussed bringing a bylaw to the floor of the NCAA convention to stop it, which never happened. In today's climate, with the rest of college football fed up with the SEC's spending and winning six straight titles, the bylaw might have passed.

The game was legal. Kramer, who was the commissioner of the SEC from 1990 to 2002, saw championship games done in the lower divisions of college football, and he had looked up the NCAA bylaw allowing for a conference championship game and kept it in his back pocket. The SEC commissioner was skewered in some columns across the South for backing this extra game. The accusations flew. It was a money grab by the conference, and it would tie a ball and chain around the league's best team.

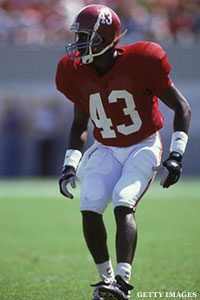

"It was a risk," Kramer said. He paused for a moment, then chuckled. "I told Antonio Langham he was my hero that week."

Langham was an Alabama defensive back. In the first SEC Championship Game on December 2, 1992, in a 21–21 game against Florida, Langham squatted on a pass route down the right hash marks. He was lying in the weeds waiting, and waiting, then jumped a pass by the Gators' Shane Mathews with 3:16 remaining in the fourth quarter. Langham snatched the pass for an interception and zigzagged his way down the Legion Field carpet for a 37-yard return for a touchdown. On this miserable night with chill and light rain, when Langham handed Alabama that 28–21 victory, Kramer slipped his head out of the noose and saw sunshine.

The Crimson Tide then went on to thump favored Miami, 34–13, to win the Sugar Bowl and claim the national championship with a 13–0 record.

Langham's interception was trumpeted as the play that saved the SEC's skin and promoted the glory of the championship game. There wasn't exactly a happy ending for the cornerback from Town Creek, Alabama, though. The next season, Langham helped Alabama to an 8-3-1 season with an all-American type year, but he got tangled up with an agent, which was against NCAA rules, and the NCAA came down on Alabama. Wins were forfeited amid sanctions and lost scholarships.

The Kramer Bowl, meanwhile, became a launching point for some SEC teams to win national championships. It was also a nationally televised game, which meant more exposure and, yes, more television money for the SEC. This big step for Goliath was another escalation of football on an academic campus, another week when students had to be athletes.

The SEC Championship Game was one last audition for voters before the final polls, and it came when many teams had finished their regular seasons. More than that, the SEC Championship Game and the eight-game schedule were booster rockets for the conference schools. Programs had to get better. They had to gear up more on Saturdays, and that meant recruiting harder and not making mistakes in recruiting. They had to raise the level of their game because of these extra conference games.

Look back at Bear Bryant's teams at Alabama. Those squads had to play just six conference games, then seven beginning in 1988 for four seasons. Sure, in some seasons Bryant scheduled Nebraska and Notre Dame, but for many years to win the SEC, the Crimson Tide, Tennessee, LSU, and all the rest had to play just six league games. Now, with eight games, it is really a gauntlet. By the time SEC teams get to the postseason, they have seen every gadget play, stonewall defenses, the best defensive linemen, hearty tailbacks, and keen-eyed coaches on the other sideline. These last six national champions, all SEC teams, have been worked over inside their own conference, and when they hit adversity in the title game, whether it was against Ohio State in January 2007 or Oregon in January 2011, they found a way to accelerate past trouble. The two extra games helped mobilize the SEC.

Just as important as adding a layer of steel with a longer SEC season, the SEC jumped out of its box as a regional football league. Until the Big 12, then the ACC and the Big Ten, and the Pac-12, added their own conference championship games, the SEC was on the national stage by itself with the SEC Championship Game in early December. When the game was moved to the Georgia Dome in 1994, it became a spectacle. Half the fans were in one school's colors, half were in another school's colors. The noise bounced off the marshmallow roof, down into the bowl, and the cheers were thunderous. National media attended the game and saw the spirit of the conference and took note.

-- Excerpted by permission from How The SEC Became Goliath: The Making of College Football's Most Dominant Conference by Ray Glier. Copyright (c) 2012 by Ray Glier. Published by Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. Available for purchase at Simon & Schuster, iTunes and Amazon.