You can't measure Woody Hayes in yards or feet, New Year's Day victories or national titles. If you did, the old man would stack up well with the best of 'em -- Bryant, Paterno, Rockne. But no, those are measuring sticks for college football's great coaches. Woody Hayes was more than a coach. To size up Hayes -- to understand how he won 205 games during his 28-year stay at Ohio State, and why, to this day, his former players abide by his life lessons -- requires measurements foreign to a football field.

Hayes was a teacher. He was a friend. He was a cheerleader for the ill and a lighthouse for the lost. He was all things great men can be. He was also controlling, quick-tempered, and, at times, irrational.

Woody Hayes may be college football's most complex subject, and yet, on the 100th anniversary of his birth (Feb. 14, 1913) and more than a quarter century since his passing, he is largely forgotten outside the state of Ohio and underappreciated by many of those working in his profession.

History judges Hayes not by success (.759 career winning percentage) or by his good deeds (too many to list, many more undocumented) but by a punch. A half-cocked right forearm, to be precise. Hayes squared up Charlie Bauman in the closing minutes of the 1978 Gator Bowl and landed a blow beneath the Clemson middle guard's chinstrap. It was his last football act -- Hayes was fired swiftly the next day -- and because of this it is what fans reference first. Say Woody Hayes and someone is sure to remind you of the punch, as if to stop dead anything good you might have to say about the man.

And they'll remind you of other incidents, too – a sideline stomp at a cameraman, a broken yard marker or two -- all of them unbecoming of what a college football coach should be, as if anyone can construct such a definition. Is a model college football coach a winner? A molder of men? A man of great integrity? Someone who shows compassion for those he coaches, both on and off the field? Hard to argue Woody was not all of those things. And yet, how many of the great coaches of today can the same be said?

For more than three decades Woody Hayes has been used as the example for what college coaches should not become -- a lesson for where greatness can go wrong. In truth, he is what the vast majority of today's coaches are no longer willing to be, yet what fans, players and administrators so desperately crave from the leader of their program.

The qualities of a good coach? See for yourself how Wayne Woodrow Hayes' portfolio stacks up ...

It's a common story about Hayes' recruiting trips. High school players expected to talk about football, but instead all Hayes spoke of was the importance of a college education. "He never said one thing to me about football," recalls legendary Ohio State running back and two-time Heisman Trophy winner Archie Griffin. "Matter of fact, when I left the meeting I really didn't think he was interested in me playing football for him and mentioned that to my father. And my father said, 'Don't you think that means he's interested in you as a person?'"

Hayes worked moms in the living room as well as anyone. "I promise you this," he'd tell them. "Your boy will get his degree." Hayes kept promises, even if it meant pestering former players. Former Ohio State President Ed Jennings' favorite story was the time he was invited to attend a 20th-year reunion for one of Hayes' famed teams. Throughout the evening Jennings kept noticing a small group of players who kept their distance from the coach. This took place all night. Finally, Jennings asked one of the other players why the group was avoiding Hayes. "Mr. President, that's easy," the player said. "They didn't graduate, and they're afraid that after 20 years Woody will make them go back to school and get their degrees."

When Moose Machinsky's grades began to fall, the 1954 All-Big Ten tackle heard a knock on his door. It was Hayes. 'Pack some clothes, get your books, and get in the car.' Machinsky became a prisoner in the Hayes' home. "He dropped me off at classes, picked me up after classes, made me study constantly, and would review my assignments and quiz me," Machinsky later shared with Ohio State beat writer Paul Hornung. "I wasn't permitted to do anything -- no dates, no movies, no TV, no beer, nothing but study. Needless to say, I worked my tail off to get out of there and not to return."

Hayes was a voracious reader himself. A naval officer in World War II, Hayes knew as much about military history as many of the academics on campus. Says 1965 co-captain Greg Lashutka, "Woody gave all of us a minor in history through the football season, drawing great analogies to what we were doing on the football field to great military battles and moments in history."

Hayes saw to it that his players got their money's worth, stopping them regularly to ask how well class was going and what they were learning about. They'd get their degree -- he'd make sure of it.

After Kern's NFL career came to an end he went back to Ohio State to work on his graduate degree. At the time he had noticed several articles about the poor academic record of student athletes around the country. Kern did his own research. "I did a longitudinal study of Woody's first 25 years of coaching at Ohio State and found that during that time football players that earned a varsity letter had a graduation rate of 87.6 percent. Of that, 37 percent went on to graduate or professional school." The numbers dwarfed the national figures Kern had been seeing in print. Excited, he headed to the practice field to share the news with his former coach. "In Woody fashion, he cocked his head a little bit, took his right hand and grabbed the corner of his glasses and said, ‘I'll be damned, I thought it was better than that. I'm going to start working tomorrow morning to improve that percentage.'"

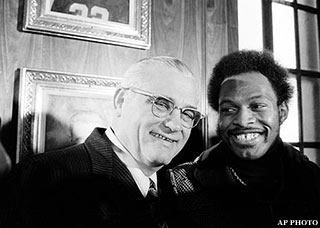

Of course, Nixon and Hayes remained close, and upon Hayes' passing in 1987 Nixon offered the eulogy. Recalling their first of many conversations, Nixon famously said, "I wanted to talk about football. Woody wanted to talk about foreign policy. You know Woody -- we talked about foreign policy."

Hayes didn't forget friends, and he didn't forget players. After losing to UCLA in the 1976 Rose Bowl, he didn't speak to the media; no one could find him. Dan Fronk, the center for Hayes' late 1950s Buckeyes teams knew where the coach was. Hayes headed straight from the airport to pay Fronk a visit. "I don't know how he got word I was in the hospital with cancer, but he came and spent five hours with me. I'll never forget it ... After all, I had graduated in 1959, and this was 1976!"

Former players in need received help, whether financial or encouragement. Kern has often told the tale about a freshman player who had been partially paralyzed from being struck on the head with a beer bottle during

a barroom dispute. He never played a down for the Buckeyes. Nearly two decades later, Hayes asked if Kern remembered the player. "We finally got him graduated," Hayes said, "and we got him a job, too!"

Coaches are not supposed to be friends with their players, and no one who played for Woody Hayes would claim they had that type of relationship with him while they wore the Scarlet and Gray. But those who gave Hayes all they had to offer during their four-year stay in Columbus were repaid with a friend for life when their careers came to an end.

Here's the thing: One story can make a hero, but with Woody the stories are endless. Hospital visits, financial contributions ... there are so many tales the magnitude of his contribution to humankind almost loses its effect, which would have been fine with Hayes. He was known to bribe nurses and hospital staff with flowers to ensure they would not tip off the media that he was there for one of his regular visits.

After beating USC in the 1969 Rose Bowl, Hayes hopped a flight for Vietnam. When he returned to Columbus he began making phone calls to the parents of the many boys he'd met. "Hi, my name is Woody Hayes," he'd begin. "I'm the football coach at the University. I spent some time in Vietnam and had a chance to visit with your son." It was important for Hayes that the parents knew their sons were fine and doing well.

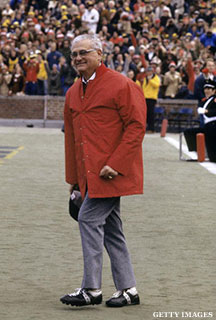

The Buckeyes secured another trip to the Rose Bowl at the end of the 1975 season after beating Michigan in Ann Arbor. Hayes was handed an armful of roses at the airport arrival gate. Ohio State's coach took a detour on his way home, giving a rose to the hospital patients who had not received a visitor that day.

"He cultivated the nasty guy image with the press. He kind of relished the role," says Jeff Kaplan, who served on Hayes' staff from 1973-75. "But that same guy would visit the hospitals twice a week."

Above all things, a great coach is an example. His words are consistent with his actions, and he never takes the easy path. Easy? Nothing Hayes did was easy -- by design. He demonstrated a work ethic no one could match, nor should attempt to. Hayes dedicated himself to film, to practice, to recruiting, and to keeping up with his players. "I can tell you there were plenty of nights he'd stay all night at the Biggs Athletic Facility," Griffin says. "He had a cot in there and he'd spend nights there. He was a workaholic, no doubt about it. He always said he may not be the best coach, but he'd outwork anybody. And he did."

"That was his competitiveness," says Kaplan, now the Executive Officer and Senior Vice President in the Office of the President at Ohio State. "It wasn't like I'm going to beat the shit out of you or I'm going to outwit you with my plays. It was I'm going to work so hard that I'm going to wear you down. I think that's where the 'three yards and a cloud of dust' came from. When we lost, it was always that we just must not have worked hard enough. We didn't put enough time in."

And Hayes expected the same from his players -- work tirelessly and the rest will take care of itself. Because of this, it left little time for his wife, Anne, and their son, Steve. The Ohio State University was his family, and he gave to it more than it could ever possibly give to him.

And even if the university had tried, Hayes would not have accepted. Money was never an influence. "He never requested, nor received, a high salary," says Kaplan. "Never asked to be the highest-paid coach in the Big Ten or top five in the country, as we do today with benchmarks for outstanding coaches. Never occurred to him. Most of the time he was in the middle or lower pack of the Big Ten coaches for pay."

Hayes' players could appreciate his work ethic and took comfort in his wisdom. President John F. Kennedy was assassinated the day before the Buckeyes were to play Michigan. The players were concerned and restless; Hayes brought perspective to a most unsettling time. "Woody talked about the peaceful transition of our country and went back to other time periods when people were shot, talked about Lincoln, talked about how strong our democracy was," says Lashutka. "At the end of it we still had heavy hearts but we had a perspective of why this country was different from others, and how we could go on, and would go on."

During Vietnam demonstrations, Hayes set his personal politics aside, taking time to listen to the students' viewpoint. When it appeared the Columbus campus was on the verge of upheaval, the school's football coach was the only authority figure able to bring calm to the students.

Most believe Hayes' life ended that night he slugged Bauman. In reality, it only ended the chapter of his coaching career. Hayes stayed loyal to Ohio State and continued to do speaking engagements to help the University, the proceeds always going to charity. The final ten years were among the richest of Hayes' life.

They allowed him more time to spend with his wife, and with their friends and his former players. He kept an office on campus and in 1986 was asked to deliver the university's graduation commencement speech. With a range of emotion, he touched on all of his favorite subjects -- military history, global politics, football – and encouraged the graduates to pay forward, a lesson he had stolen from Ralph Waldo Emerson and preached regularly to his men at practice. He even inserted a little humor: " ... there have been a lot of great men fired -- MacArthur, Richard Nixon, a lot of them."

Hayes called this the greatest day of his life. It signified acceptance as an educator, perhaps. For much of his life that's what Hayes was -- an educator. Like Lombardi, he helped young men find their way. And like Lombardi's men, the men of Woody Hayes continue to carry him in their daily lives: Whenever Griffin speaks, he makes a point to mention Hayes; Lashutka's children were often reminded that 'Nothing in life comes easy'; remembering Woody's words about Nixon, Kaplan has never left a friend in need behind.

Says Kern, "Same as Lombardi's players would say about Lombardi ... Woody was our guy and we'd defend him to the hilt."

And they do. Often. Too bad they should have to.

-- Mike Beacom is the author of Ohio State Football: Yesterday & Today and the Complete Idiot's Guide to Understanding Football. Follow him on Twitter @mikebeacom.