John U. Bacon is the author of "EndZone: The Rise, Fall, and Return of Michigan Football," which was released in September 2015 and now available in paperback with 57 additional pages.

When dawn broke on Friday, November 17, 2006, the Michigan Wolverines stood atop the college football world.

They had notched the most wins in the sport's history (871), the highest winning percentage (.735), and the most conference titles (43) in the sport's oldest, most storied league. They could boast the biggest stadium (107,501), the largest crowds -- exceeding 100,000 for 251 straight games, going back to 1975 -- the biggest revenues and, many believed, the most respect.

That morning, the Wolverines stood at 11–0, and were ranked second in the nation. A win over top-ranked Ohio State the next day, in the first "Game of the Century," would give them a shot at a twelfth national title, which would provide a fine springboard for the complete renovation of the stadium, ensuring the Big House would remain the nation's biggest and most profitable, for years to come.

In Ann Arbor, life couldn't get much better.

Shortly before noon that Friday morning, Bo Schembechler died from heart failure. For Michigan fans, the bad news lasted almost a decade.

The next day, Michigan lost a nail-biter, 42–39, to Ohio State -- then dropped the next three straight, including the 2007 season opener against Appalachian State, still considered the greatest upset in the history of college football.

When head coach Lloyd Carr retired after that season, Michigan hired Rich Rodriguez, whose rocky three-year run produced a 15–22 record and a fractured fan base. In 2011, little-known Brady Hoke replaced Rodriguez and enjoyed a honeymoon season when the Wolverines beat the Buckeyes for the first time in eight years, and won a BCS bowl for the first time in twelve, to finish 11–2. But the following season, 2012, the Wolverines slid to 8-5, then 7-6 and 5-7 the next two seasons.

What went so wrong, so fast?

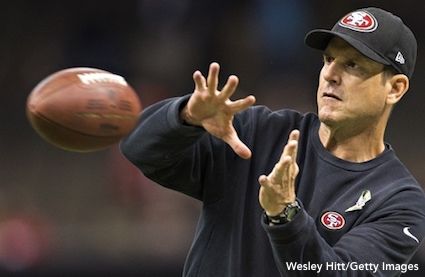

Despite two straight bad seasons, heading into the 2014 season, Brady Hoke seemed poised for a solid season, and maybe a great one. On the West Coast, everyone expected Jim Harbaugh's 49ers to make their fourth straight trip to the playoffs, if not the NFC title game.

The idea that Harbaugh would return to his alma mater any time soon seemed absurd. And even if Michigan's head coaching position somehow magically opened, many people weren't sure if Harbaugh would want it.

But one of these impediments, at least, was not what it appeared.

On Friday, July 18, 2014, Jim and Sarah Harbaugh traveled to northern Michigan to spend the evening with Todd Anson, a San Diego attorney, friend and occasional adviser, Todd's wife, Terri, and a dozen or so of Anson's friends, including yours truly. I had gotten to know Todd while researching my previous two books. After some appetizers and cocktails, the entire party boarded the S.S. Boike, a pontoon boat with ample bench seating and a couple of coolers.

The boat's owner, Bill Boike, a Michigan-trained neurologist, donned his captain's hat and guided the boat through some narrows in a no-wake zone near the Ironton Ferry. Boike just happened to have a recording of "The Victors" handy, and couldn't resist blaring it through the speakers, "just to welcome Jim to our little piece of heaven," Boike told me later. "Jim's response was awesome. With no hesitation and unabashed enthusiasm he joined in, fist pumping in the air, singing at the top of his lungs. He was obviously one of us -- an ardent supporter of our great university with a deep affection for the maize and blue."

The passengers hadn't gotten too far into Michigan's fight song when Boike's boat encountered another boat with a few Spartans on it, and their green flag flying high. It turned out they just happened to have their own fight song ready to blast in response to "The Victors," while the two boats raced down the lake. But the S.S. Boike had more volume and more passengers, and eventually won the battle of the bands.

"No one enjoyed the exchange more than Jim," Boike said, "who told us that's what he loved about college rivalries. ‘This stuff just doesn't happen in the NFL.'" Sarah later recalled, "Jim told me, 'You've got to learn this song!' "

"Our Spartan friends turned their boat around," Boike recalls, "and a young lady stood up and proudly mooned us as they took off."

When the passengers on Boike's boat that night later heard and read various experts say there was no way the Harbaughs would ever leave California and the NFL for Michigan, they knew better. They had seen it firsthand.

"Jim was sooo happy," Sarah told me later. "It was easy to see he still felt very much connected, and excited!"

Most of the guests left about 10, but Todd, Jim and I stayed up until 2 a.m., catching up and talking about mutual friends, Ann Arbor and Michigan football.

In the middle of our conversation, Harbaugh said, "I think it's great to grow up in a college town, don't you?"

"That," Anson said later, "was the first sign I had that I might be right about Jim's 'manifest destiny.' "

"He's said that many times to me," Sarah later told me. "'Wouldn't it be great to raise our kids in a college town?' Palo Alto is great, but it's not really a college town like Columbia [Missouri, home of her alma mater], like Ann Arbor. That's always been in the back of his mind."

There was still a mountain of obstacles between Harbaugh and the Michigan coaching job. Only a lunatic would have made that bet. But that night, two bits of conventional wisdom -- that the Harbaughs were unwilling to leave California and the NFL, and had no interest in Michigan -- were revealed to be illusions. They did not exist.

In fact, the opposite was true. Harbaugh had never lost his feeling for Michigan, and his desire to coach there was as strong as ever.

That meant only the mountain of obstacles between him and Michigan remained.

The first was Brady Hoke, who was expected to have a break-out season. But in Michigan's second game against Notre Dame stunned the Wolverines, 31-0.

The whitewash was Notre Dame's first shutout of the Wolverines since the Irish played their first game in 1887. It also snapped Michigan's NCAA-record streak of games without being shut out at 365.

"Michigan had lost games before," three-term Regent Larry Deitch said, looking back on the 2014 season, "but not like this. We didn't appear to be competitive."

In Hobe Sound, Florida, John Arbeznik, captain of the 1979 Michigan team, watched the game at his home.

"I could not believe what I was seeing. I was miserable after the blowout and felt semi-helpless," Arbeznik told me. "I knew Les Miles, among others, wanted the job. I was reaching out to Jim for two reasons: To fill him in on our efforts to fix Michigan football, and second, to see if he would support our candidates."

He did not believe Harbaugh himself might be a candidate for the job. Harbaugh didn't answer, so Arbeznik left a message.

"I was almost crying," Arbeznik admits. "I was still distressed by the effort the previous night. I told Jim, 'We need help. You're Michigan.' I wasn't expecting to pitch the job to him, but get his help getting Les back. But I even said on the message that I would cut off my right hand if he would be our next coach."

That's how big a long shot it seemed, and how desperate Arbeznik and his friends were to see Jim Harbaugh return.

"Thank God he didn't take me up on that!"

When Harbaugh returned his call, Arbeznik realized their dream might not be so crazy after all.

Just four years into Brandon's tenure, the money had started drying up, the fans stopped filling the Big House, and just about everyone was bailing on Brandon's vision.

In October of 2014, three days after quarterback Shane Morris left the Minnesota game with a "probable, mild concussion," the students held a campus rally outside the home of recently hired President Mark Schlissel to demand he fire Dave Brandon. It was not simply the 2014 team's 2–3 record to that point that had them upset, or they would have been asking for Hoke to be fired, not Brandon. It went deeper than that: They no longer had confidence the athletic director represented the values of the university they loved.

In different ways and at different times, the many constituents of Michigan football reached the same conclusion: This is not Michigan.

Something had to give. But could anyone make the needed changes fast enough to prevent a truly disastrous 2015 season, on and off the field, and avoid missing out on Michigan's slim chance to hire Jim Harbaugh?

The pro-Harbaugh faction – which included just about everyone who cared about Michigan football – received an unexpected break on Tuesday, October 28, when Brandon's insulting emails to fans were published on MGoBlog, one of the biggest fansites in the country. Many of Brandon's phrases, such as, "Get another team. We'll be fine with out you," and "Have a happy life," recurred in his responses, suggesting a strong pattern. Another email he ended by saying, "Quit drinking and go to bed," which was so comically out of line it was printed on a popular T-shirt, in the same format as the trendy "Keep Calm and Carry On" T-shirt.

Regent Larry Deitch said, "It's possible that if the emails had not come out, that there could have been a different result. It was still headed in that direction, but he might have been able to save himself. When the emails came out, however, Mark [Schlissel] knew what he had to do. I honestly don't know what choice he had."

One night later, Brandon resigned. One month later, Hoke finished his fourth season with a 5-7 record.

Since the day Schembechler died eight years earlier to Hoke's firing on December 2, 2014, mighty Michigan had gone 55-48 overall, and 24-33 in the Big Ten -- not the kind of numbers that had made Michigan the envy of its peers. When the football program collapsed into almost unrecognizable mediocrity, its fall pulled the university itself into conflict, controversy and crisis.

But by December of 2014, Brandon had been replaced by interim athletic director Jim Hackett, who had played for Schembechler in the seventies, before embarking on a 20-year run as CEO of Steelcase Furniture. With both Brandon and Hoke out of the way, the door was open for Harbaugh to return – if he wanted to. But would he?

Most experts believed Harbaugh wouldn't, mainly because he didn't seem to want the job when Brandon finished his coaching search in 2011 by hiring Hoke, not Harbaugh.

"I do believe Dave wanted Harbaugh," a member of Brandon's leadership team told me, "but he wanted Jim on his terms." What were Brandon's terms?

Many believe Brandon did not want to hire someone whom he could not control, or outshine, and there is little question that Harbaugh would draw more attention and be more strong-willed than a lesser-known candidate like Hoke. Brandon, intentionally or not, sent this conditional message to Harbaugh when he did not make a decision on Rodriguez sooner, rarely contacted Harbaugh, and declined to visit Harbaugh in person -- sending not Michigan's highly paid search consultant Jed Hughes, either, but Hughes's subordinate, a young man named Philip Murphy, who graduated from Notre Dame in 1999 and the Wharton School of Business four years earlier. All this told Harbaugh that Brandon was not dying to bring him back.

Harbaugh decided trying to return to Ann Arbor in 2011 was not his best move.

After Harbaugh signed with the 49ers, Todd Anson asked Harbaugh if he really had been interested in the Michigan job. Harbaugh paused, then replied, "I just wasn't feelin' the love."

And that's what it came down to. Not money. Not power. Not fame -- but love. And Michigan, under Brandon, wasn't offering it to Harbaugh.

But with the job open again in 2014, and the considerable impediment of Brandon gone, a group of lettermen, insiders and Harbaugh allies went to work to pave the way for Harbaugh to return. Encouraged by the mere fact that Jim Harbaugh hadn't instantly killed the idea of one day coaching at Michigan, Harbaugh's unofficial ambassadors went to work. The effort was led by Todd Anson in California, John Arbeznik in Florida, lifelong Harbaugh friend Robbie Pollock in Ann Arbor, and former Michigan lineman John Ghindia in the Detroit suburbs, who was in constant communication with the other two, and just about everyone else.

"Brandon never got it," Anson says. "I said many times to the people involved, 'It takes a village to hire a superstar football coach.'"

The growing village of ambassadors trying to get Jim Harbaugh back to Michigan seemed to be guided by a few basic principles. Their plan, boiled down, was simply this: Whatever Brandon had done during his coaching search in 2011, they would do the exact opposite.

Don't play games. Be direct.

Don't hold back. Show the love.

Don't do it yourself. Get help.

Don't worry about who gets the credit. Harbaugh's return would be credit enough for everybody.

"You know there's an old saying," Regent Larry Deitch told me. "'It's kind of amazing what you can accomplish when no one cares who gets the credit.' And that's what happened here. It was teamwork!

"Flame and Ghindia, I met them years ago through my good friend Dan Horning [a former Regent]. Those guys were completely sincere. They were completely credible. They just wanted Michigan to be good so they could be proud of it, and they wanted respect for the people who worked very hard to build the Michigan football tradition."

A grassroots effort had begun. No one in the loosely organized group was in it for money, fame, power, or even credit. The proof is simple: You've probably never heard of most of these people, or what they did, until now. They simply wanted to see Michigan football return to its former heights, and they believed Jim Harbaugh was the man to get them back there.

"All we wanted to do was create the marketplace where both sides wanted to buy," Ghindia told me, "so all Michigan had to do was get in front of Harbaugh, and make their pitch."

They still had far more work in front of them than behind them, and even if they completed their mission, the odds were still long. But they had made two vital decisions: To take action, and to work together -- two elements that were crucially missing in 2011.

As soon as Hackett announced Hoke's departure, they could work more openly, but so could Harbaugh's detractors. When the rumor mill kicked into overdrive, they did, too.

"After Michigan fired Coach Hoke," recalls Jay Flannelly, a former team manager from the 1990s who remains close to the lettermen, "someone was leaking to the media that Jim could not leave California due to custody issues from his first marriage. I called [former lineman John] Ghindia and someone else who knows these types of things -- and all of it came back the same: It was all untrue! But again, people were trying to sabotage our program with nonsense and jealousy. We all felt we couldn't let that happen again."

Another popular rumor held that Sarah Harbaugh wouldn't leave California. Anyone who had talked to her would know that was also completely false. Contrary to the rumor mill, which often depicted Sarah Harbaugh as some kind of Las Vegas model attracted to Jim's money and fame, who refused to leave California for Michigan, the former Sarah Feuerborn (pronounced "Fear-Born") is not from Las Vegas, but Kansas City, the youngest of 11 children, whose father was an accountant at General Motors. She earned her degree in education from the University of Missouri, then moved to Las Vegas because teaching jobs were easier to get there.

After a few years teaching, a friend approached her about working in real estate. When her first deal earned her more money than she had earned in an entire year of teaching, she made a career change. By the time she met Jim, in 2006, she was already earning twice his salary at the University of San Diego, where he lived in a cramped, low-rent home near the water. In short, she didn't marry him for his money, and she didn't know who he was until her brother John told her.

She had only been to Michigan twice -- once for Schembechler's funeral, and once for Harbaugh's player's wedding -- but she loved it both times. She was not about to stop her husband from taking a job in Ann Arbor.

The Anson playbook dictated that they pounce on any false rumors, then immediately go back on offense. Passivity was not part of the plan.

True, a lot of people did a lot of work behind the scenes to increase the odds, and crucially, Lloyd Carr publicly and privately encouraged Harbaugh's return, and urged his former players to do the same. But they still needed a lot of breaks just to make it possible.

In Ann Arbor, the departures of Brandon and Hoke were essential, of course. But in San Francisco, Michigan fans had some unlikely, unwitting, allies.

"No one," Anson told me, "could have orchestrated the perfect storm of bad management with the 49ers, and then at Michigan, too. Those both played right into our hands."

The lucky breaks didn't stop there.

Jay Flannelly, the former team manager turned dishwasher at Pizza House, known as "The Beav" by the former players, knew he could ask his longtime friend Tom Brady for almost anything -- except after a loss. The Sunday after the Michigan-Ohio State game, November 30, the Patriots suffered only their third defeat of the season at Green Bay. Flannelly wasn't going to bother asking a favor after that one.

But on December 7, the Patriots got back to their winning ways in San Diego, beating the Chargers, 23-14, to go 10-3 on the season.

The Beav sprang into action.

"The Pats won, and Tom played great," Flannelly told me. "So after the game's over, I'm emailing Tom. I congratulate him on the win. He replies, 'Hey, we won, we played great.' Then I ask him to call Harbaugh, and give Tom his number. Tom says, ‘Coach Harbaugh is the kind of guy we need.'

"Next day, Ghindy tells me Tom called Jim and talked for two hours. Okay, that's really cool."

"Tom Brady," Ghindia says, "has as much to do with Harbaugh coming back as any player on our list. It showed Jimmy just how deep it went."

Despite everyone's eagerness to help, and the flood of calls to Harbaugh that followed, Flannelly still wasn't convinced it would be enough.

"I'm still thinking, there's still no way this is going to happen," he admits. "But Ghindy says, ‘Keep it up! Keep it up! Keep it up! You're doing a great job, and it's working!'

"So, I kept it up. We all did!"

In fact, Ghindia was right: It was working.

"I was aware of all the calls coming in," Sarah Harbaugh told me. "It was really neat -- neat to see a whole group of people coming together and really pushing for him. It was a little overwhelming in a sense, but that made it that much harder to say no -- not that there was ever a question."

"Everyone's calling Jim," Anson says. "Ghindy would call me every day, sometimes 20 times. And it was always, ‘Okay, who's next? Okay, what's next?'

"Man, Ghindia was all over this thing!

"'Who's next?!'"

The good vibrations Team Harbaugh generated over Harbaugh's birthday and Christmas were helpful, but all the texts in the world couldn't be confused with a contract.

That was Hackett's job. At one point during the weekly conversations Hackett made to Harbaugh, "I shared with him my time line," Hackett says. "'Here's my walk-away date: Saturday, December 27, 2014.' "

Day by day, it became clearer to Hackett that Harbaugh was sincerely interested in leading Michigan's program, and Harbaugh certainly didn't have to wonder if Hackett, or just about anyone else who mattered, wanted him to do so.

Proving the early rumors false, Sarah was on board, with both feet. When Anson's army of friends, former teammates, and childhood idols started calling Jim, and even saying on TV how much they wanted him back in Ann Arbor, "That's when I said, 'Wow, they really want you!' " Sarah recalls telling her husband. "'Very few people can do that in a lifetime, be that person that everyone wants. You gotta go!'

"A lot of people say, 'You made it to the top, you've got to stay at the top,' " she told me. "Not that he's taking a step down by coming to Michigan, but he's pursuing something that he always he felt was his destiny.

"It happened so fast, I was in shock. But not for one minute did I not see the good in coming to Ann Arbor. We were in a great place, but I'm coming back home in a sense. I'm Midwestern, and I always will be.

"It was such a fragile process for everyone. If it had not been handled just that way -- if you had someone who was pushing you, not letting you make the decision, not giving you your space -- I don't think it would have happened.

"Feeling the love. That's what it came down to."

When I asked Harbaugh about this, he said, "Let's not make this sound more noble than it is. I'm not on the same dance floor as Mother Teresa. I like a buck as much as the next guy. I wouldn't kill for it, I wouldn't marry for it, I wouldn't cheat for it, I wouldn't steal for it. But I'm open to earning it.

"But," he added, "I would say that I didn't pick Michigan because I thought they were going to pay me the most. We didn't wait around for teams to start some bidding war, or even make offers."

The decision wasn't easy, but it was simple.

"Earlier that week, I was talking to my dad on the phone, and I finally cut to the chase. ‘Well, whatya think, Dad?' "

"Well, Jim," his dad said, "you make great decisions; you always have. I'm not going to tell you what to do. Follow your heart."

"And that," Jim Harbaugh said, "is what I did."

Almost exactly ten years after Schembechler passed away, the Big House is full. The Michigan Wolverines are 10-1, ranked third, and about to take on the second-ranked Buckeyes, for all the marbles.

It only took Michigan a decade to find one of Bo's boys to lead them back.

John U. Bacon is the author of four New York Times bestsellers. His latest book, Endzone: The Rise, Fall and Return of Michigan Football, is now available in paperback with an update covering the 2015 season and 2016 off-season. He gives weekly commentary on Michigan Radio, teaches at the University of Michigan and Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism, and speaks nationwide on leadership and diversity. Learn more at JohnUBacon.com, and follow him on Twitter @johnubacon.